- Home

-

Screening

- Ionic Screening Service

-

Ionic Screening Panel

- Ligand Gated Ion Channels

- Glycine Receptors

- 5-HT Receptors3

- Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors

- Ionotropic Glutamate-gated Receptors

- GABAa Receptors

- Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulators (CFTR)

- ATP gated P2X Channels

- Voltage-Gated Ion Channels

- Calcium Channels

- Chloride Channels

- Potassium Channels

- Sodium Channels

- ASICs

- TRP Channels

- Other Ion Channels

- Stable Cell Lines

- Cardiology

- Neurology

- Ophthalmology

-

Platform

-

Experiment Systems

- Xenopus Oocyte Screening Model

- Acute Isolated Cardiomyocytes

- Acute Dissociated Neurons

- Primary Cultured Neurons

- Cultured Neuronal Cell Lines

- iPSC-derived Cardiomyocytes/Neurons

- Acute/Cultured Organotypic Brain Slices

- Oxygen Glucose Deprivation Model

- 3D Cell Culture

- iPSC-derived Neurons

- Isolation and culture of neural stem/progenitor cells

- Animal Models

- Techinques

- Resource

- Equipment

-

Experiment Systems

- Order

- Careers

Retinitis Pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of related eye diseases that cause progressive vision loss. These diseases affect the light-sensitive tissue layer at the back of the eye, the retina. In patients with retinitis pigmentosa, vision loss occurs as the photoreceptor cells of the retina gradually degenerate.

The first symptom of retinitis pigmentosa is usually decreased night vision, which is obvious in childhood. Night vision problems may make it difficult to recognize directions in low light. Later, this disease can cause blind spots in the field of vision. Over time, these blind spots merge to produce tunnel vision. This disease can develop for years or decades, affecting central vision, which is necessary for detailed tasks such as reading, driving, and recognizing faces. After adulthood, many people with retinitis pigmentosa become blind.

The symptoms and signs of retinitis pigmentosa are mostly manifested as decreased vision. When the disease itself occurs, it is generally described as non-syndromic. Researchers have identified several major types of non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa, which are usually distinguished according to their inheritance patterns: autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and X-linked. Rarely, retinitis pigmentosa occurs as part of a syndrome that affects other organs and tissues of the body. These forms of disease are described as syndromes. The most common syndrome of retinitis pigmentosa is Usher syndrome, which is characterized by vision loss and hearing loss early in life. Retinitis pigmentosa is also a feature of several other genetic syndromes, including Bardet-Biedl syndrome, Refsum disease, neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa (NARP).

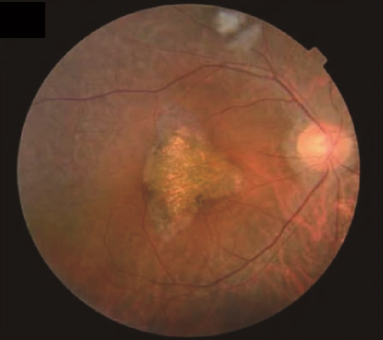

Figure 1. Fundus photographs of individuals examined for retinitis pigmentosa.(Nadeem, R., et al.; 2020)

Pathogenesis

Clinical studies have found that mutations in more than 60 genes can cause non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa.

Among them, more than 20 genes are related to the autosomal dominant form of the disease. Rhodopsin (RHO) gene mutations are the most common cause of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa, accounting for 20% to 30% of all cases. The RHO gene is a gene encoding rhodopsin protein. Rhodopsin is present in rod cells. As part of the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye (retina), the rod provides vision in low light. Other photoreceptor cells in the retina, called cones, are responsible for vision in bright light. Rhodopsin protein attaches (binds) to a molecule called 11-cis retina, which is a form of vitamin A. When light irradiates the molecule, it activates rhodopsin and initiates a series of chemical reactions, generating electrical signals. These signals are transmitted to the brain, where they are interpreted as vision. Mutations in the rhodopsin gene destroy the rhodopsin that is necessary for the conversion of light into recognizable electrical signals in the central nervous system's phototransduction cascade. The activity defects of this G protein coupled receptor can be divided into different categories, depending on the specific folding abnormalities and the resulting molecular pathway defects. The activity of class I mutant proteins is affected by specific point mutations in the protein-encoded amino acid sequence, which affects the transport of pigment proteins into the outer segment of the eye, and the phototransduction cascade is located in the outer segment of the eye. The misfolding of the class II rhodopsin gene mutation disrupts the binding of the protein to the 11cis-retina. Other mutations in this pigment-encoding gene will affect the stability of the protein, destroy the integrity of the mRNA after translation, and affect the activation rate of transduced proteins and opsins.

At least 35 genes are involved in the autosomal recessive inheritance of the disease. The most common of these is USH2A; mutations in this gene account for 10% to 15% of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa cases. The USH2A gene provides instructions to make a protein called usherin. Usherin is an important part of the basement membrane, which is a thin sheet-like structure that can separate and support cells in many tissues. Usherin is located in the basement membrane of the inner ear and retina. Although the function of usherin is not yet fully established, studies have shown that it is part of a group of proteins (a protein complex) that plays an important role in the development and maintenance of inner ear and retinal cells. Protein complexes may also be involved in the function of synapses, which are connections between nerve cells where cell-to-cell communication occurs.

Changes in at least six genes are believed to cause the X-linked form of the disease. Among them, the mutated genes in RPGR and RP2 account for most cases of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa.

References

- Daiger SP, et al.; Perspective on genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007, 125(2):151-8.

- Daiger SP, et al.; Mutations in known genes account for 58% of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (adRP). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008, 613:203-9.

- Pelletier V, et al.; Comprehensive survey of mutations in RP2 and RPGR in patients affected with distinct retinal dystrophies: genotype-phenotype correlations and impact on genetic counseling. Hum Mutat. 2007, 28(1):81-91.

- Nadeem, R., et al.; Mutations in CERKL and RP1 cause retinitis pigmentosa in Pakistani families. Hum Genome Var . 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41439-020-0100-8.

Related Section

Inquiry